C C++ Learning Note

C/C++ 学习笔记。

自己因为不是科班出身,C/C++,Python的基础都不够好。只能遇到不懂,就查一查记录下来。这次在这里记录的,也都是想看tinyflow,nnvm里面的内存管理部分,而遇到的新知识。

C语言中.h文件和.c文件详细解析

简单来说:

- 这样做目的是为了实现软件的模块化

- 使软件结构清晰,而且也便于别人使用你写的程序

- 纯粹用 C 语言语法的角度,你当然可以在 .h 中放任何东西,因为 #include

完全等价于把 .h 文件 **Ctrl-C Ctrl-V** 到 .c 中 - .h 中应该都是一些宏定义和变量、函数声明,告诉别人你的程序“能干什么、该怎么用”

- .c 中是所有变量和函数的定义,告诉计算机你的程序“该怎么实现”

- .h只做声明,编译后不产生代码

- .c和.h文件没有必然的联系.

- 一般的数据,数据结构,接口,还有类的定义放在.h文件中,可以叫他们头文件,可以#include 到别的文件中。功能实现一般都放在具体的.cpp文件中。

具体来说:

简单讲,一个Package就是由同名的.h和.cpp文件组成。当然可以少其中任意一个文件:只有.h文件的Package可以是接口或模板(template)的定义;只有.cpp文件的Package可以是一个程序的入口(学习资料.ppt)。

头文件格式

头文件的所有内容,都必须包含在

#ifndef {Filename}

#define {Filename}

// {Content of head file}

#endif

这样才能保证头文件被多个其他文件引用(include)时,内部的数据不会被多次定义而造成错误.

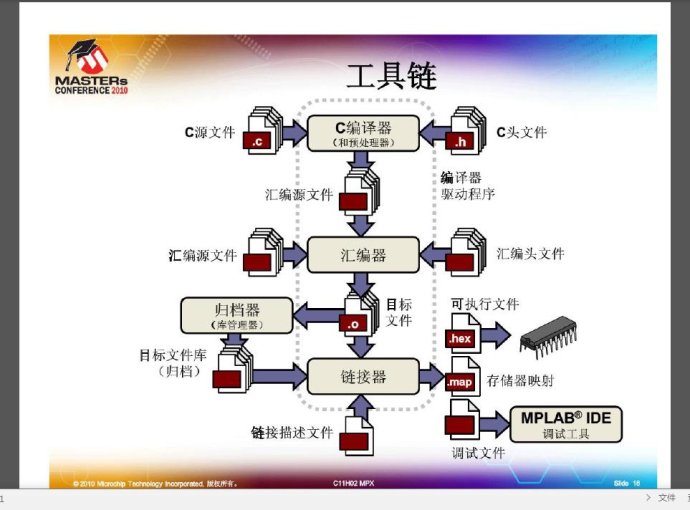

简单的说其实要理解C文件与头文件(即.h)有什么不同之处,首先需要弄明白编译器的工作过程,一般说来编译器会做以下几个过程:

1.预处理阶段

2.词法与语法分析阶段

3.编译阶段,首先编译成纯汇编语句,再将之汇编成跟CPU相关的二进制码,生成各个目标文件 (.obj文件)

4.连接阶段,将各个目标文件中的各段代码进行绝对地址定位,生成跟特定平台相关的可执行文件,当然,最后还可以用objcopy生成纯二进制码,也就是去掉了文件格式信息。(生成.exe文件)

编译器在编译时是以C文件为单位进行的,也就是说如果你的项目中一个C文件都没有,那么你的项目将无法编译,连接器是以目标文件为单位,它将一个或多个目标文件进行函数与变量的重定位,生成最终的可执行文件,在PC上的程序开发,一般都有一个main函数,这是各个编译器的约定,当然,你如果自己写连接器脚本的话,可以不用main函数作为程序入口。

有了这些基础知识,再言归正传,为了生成一个最终的可执行文件,就需要一些目标文件,也就是需要C文件,而这些C文件中又需要一个main函数作为可执行程序的入口,那么我们就从一个C文件入手,假定这个C文件内容如下:

#include

#include "mytest.h"

int main(int argc,char **argv)

{

test = 25;

printf("test.................%d\n",test);

}

mytest.h头文件内容如下:

int test;

现在以这个例子来讲解编译器的工作:

1.预处理阶段:编译器以C文件作为一个单元,首先读这个C文件,发现第一句与第二句是包含一个头文件,就会在所有搜索路径中寻找这两个文件,找到之后,就会将相应头文件中再去处理宏,变量,函数声明,嵌套的头文件包含等,检测依赖关系,进行宏替换,看是否有重复定义与声明的情况发生,最后将那些文件中所有的东东全部扫描进这个当前的C文件中,形成一个中间”C文件”

2.编译阶段,在上一步中相当于将那个头文件中的test变量扫描进了一个中间C文件,那么test变量就变成了这个文件中的一个全局变量,此时就将所有这个中间C文件的所有变量,函数分配空间,将各个函数编译成二进制码,按照特定目标文件格式生成目标文件,在这种格式的目标文件中进行各个全局变量,函数的符号描述,将这些二进制码按照一定的标准组织成一个目标文件

3.连接阶段,将上一步成生的各个目标文件,根据一些参数,连接生成最终的可执行文件,主要的工作就是重定位各个目标文件的函数,变量等,相当于将个目标文件中的二进制码按一定的规范合到一个文件中。 再回到C文件与头文件各写什么内容的话题上:理论上来说C文件与头文件里的内容,只要是C语言所支持的,无论写什么都可以的,比如你在头文件中写函数体,只要在任何一个C文件包含此头文件就可以将这个函数编译成目标文件的一部分(编译是以C文件为单位的,如果不在任何C文件中包含此头文件的话,这段代码就形同虚设),你可以在C文件中进行函数声明,变量声明,结构体声明,这也不成问题!!!那为何一定要分成.h 头文件与C文件呢?又为何一般都在头件中进行函数,变量声明(函数原型),宏声明,结构体声明呢?而在C文件中去进行变量定义,函数实现呢??原因如下:

1.如果在头文件中实现一个函数体,那么如果在多个C文件中引用它,而且又同时编译多个C文件,将其生成的目标文件连接成一个可执行文件,在每个引用此头文件的C文件所生成的目标文件中,都有一份这个函数的代码,如果这段函数又没有定义成局部函数,那么在连接时,就会发现多个相同的函数,就会报错。

2.如果在头文件中定义全局变量,并且将此全局变量赋初值,那么在多个引用此头文件的C文件中同样存在相同变量名的拷贝,关键是此变量被赋了初值,所以编译器就会将此变量放入DATA段,最终在连接阶段,会在DATA段中存在多个相同的变量,它无法将这些变量统一成一个变量,也就是仅为此变量分配一个空间,而不是多份空间,假定这个变量在头文件没有赋初值,编译器就会将之放入 BSS段,连接器会对BSS段的多个同名变量仅分配一个存储空间

3.如果在C文件中声明宏,结构体,函数等,那么我要在另一个C文件中引用相应的宏,结构体,就必须再做一次重复的工作,如果我改了一个C文件中的一个声明,那么又忘了改其它C文件中的声明,这不就出了大问题了,程序的逻辑就变成了你不可想象的了,如果把这些公共的东东放在一个头文件中,想用它的C文件就只需要引用一个就OK了!!!这样岂不方便,要改某个声明的时候,只需要动一下头文件就行了

4.在头文件中声明结构体,函数等,当你需要将你的代码封装成一个库,让别人来用你的代码,你又不想公布源码,那么人家如何利用你的库呢?也就是如何利用你的库中的各个函数呢??一种方法是公布源码,别人想怎么用就怎么用,另一种是提供头文件,别人从头文件中看你的函数原型,这样人家才知道如何调用你写的函数,就如同你调用printf函数一样,里面的参数是怎样的??你是怎么知道的??还不是看人家的头文件中的相关声明啊.

而且,比方说 我在aaa.h里定义了一个函数的声明,然后我在aaa.h的同一个目录下建立aaa.c ,aaa.c里定义了这个函数的实现,然后是在main函数所在.c文件里#include这个aaa.h 然后我就可以使用这个函数了。 main在运行时就会找到这个定义了这个函数的aaa.c文件。

这是因为:

main函数为标准C/C 的程序入口,编译器会先找到该函数所在的文件。

假定编译程序编译myproj.c(其中含main())时,发现它include了mylib.h(其中声明了函数void test()),那么此时编译器将按照事先设定的路径(Include路径列表及代码文件所在的路径)查找与之同名的实现文件(扩展名为.cpp或.c,此例中为mylib.c),如果找到该文件,并在其中找到该函数(此例中为void test())的实现代码,则继续编译;如果在指定目录找不到实现文件,或者在该文件及后续的各include文件中未找到实现代码,则返回一个编译错误.其实include的过程完全可以”看成”是一个文件拼接的过程,将声明和实现分别写在头文件及C文件中,或者将二者同时写在头文件中,理论上没有本质的区别。

以上是所谓动态方式。

此外:从C编译器角度看,.h和.c皆是浮云,就是改名为.txt、.doc也没有大的分别。换句话说,就是.h和.c没啥必然联系。.h中一般放的是同名.c文件中定义的变量、数组、函数的声明,需要让.c外部使用的声明。这个声明有啥用?只是让需要用这些声明的地方方便引用。因为 #include “xx.h” 这个宏其实际意思就是把当前这一行删掉,把 xx.h 中的内容原封不动的插入在当前行的位置。由于想写这些函数声明的地方非常多(每一个调用 xx.c 中函数的地方,都要在使用前声明一下子),所以用 #include “xx.h” 这个宏就简化了许多行代码–让预处理器自己替换好了。

程序编译的时候,并不会去找b.cpp文件中的函数实现,只有在link的时候才进行这个工作。我们在b.cpp或c.cpp中用#include “a.h”实际上是引入相关声明,使得编译可以通过,程序并不关心实现是在哪里,是怎么实现的。源文件编译后成生了目标文件(.o或.obj文件),目标文件中,这些函数和变量就视作一个个符号。在link的时候,需要在makefile里面说明需要连接哪个.o或.obj文件(在这里是b.cpp生成的.o或.obj文件),此时,连接器会去这个.o或.obj文件中找在b.cpp中实现的函数,再把他们build到makefile中指定的那个可以执行文件中。

C++模板 template

C++模板

模板是C++支持参数化多态(int, double)的工具,使用模板可以使用户为类或者函数声明一种一般模式,使得类中的某些数据成员或者成员函数的参数、返回值取得任意类型。

模板是一种对类型进行参数化的工具;

通常有两种形式:函数模板和类模板;

函数模板针对仅参数类型不同的函数;

类模板针对仅数据成员和成员函数类型不同的类。

使用模板的目的就是能够让程序员编写与类型无关的代码。比如编写了一个交换两个整型int 类型的swap函数,这个函数就只能实现int 型,对double,字符这些类型无法实现,要实现这些类型的交换就要重新编写另一个swap函数。使用模板的目的就是要让这程序的实现与类型无关,比如一个swap模板函数,即可以实现int 型,又可以实现double型的交换。模板可以应用于函数和类。下面分别介绍。

注意:模板的声明或定义只能在全局,命名空间或类范围内进行。即不能在局部范围,函数内进行,比如不能在main函数中声明或定义一个模板。

一、函数模板通式

1、函数模板的格式:

template <class 形参名,class 形参名,......> 返回类型 函数名(参数列表)

{

函数体

}

其中template和class是关键字,class可以用typename 关键字代替,在这里typename 和class没区别,<>括号中的参数叫模板形参,模板形参和函数形参很相像,模板形参不能为空。一但声明了模板函数就可以用模板函数的形参名声明类中的成员变量和成员函数,即可以在该函数中使用内置类型的地方都可以使用模板形参名。模板形参需要调用该模板函数时提供的模板实参来初始化模板形参,一旦编译器确定了实际的模板实参类型就称他实例化了函数模板的一个实例。比如swap的模板函数形式为

template <class T> void swap(T& a, T& b){

},

当调用这样的模板函数时类型T就会被被调用时的类型所代替,比如swap(a,b)其中a和b是int 型,这时模板函数swap中的形参T就会被int 所代替,模板函数就变为swap(int &a, int &b)。而当swap(c,d)其中c和d是double类型时,模板函数会被替换为swap(double &a, double &b),这样就实现了函数的实现与类型无关的代码。

二、类模板通式

1、类模板的格式为:

template<class 形参名,class 形参名,…> class 类名

{ ... };

类模板和函数模板都是以template开始后接模板形参列表组成,模板形参不能为空,一但声明了类模板就可以用类模板的形参名声明类中的成员变量和成员函数,即可以在类中使用内置类型的地方都可以使用模板形参名来声明。比如

template<class T> class A{

public:

T a;

T b;

T hy(T c, T &d);};

在类A中声明了两个类型为T的成员变量a和b,还声明了一个返回类型为T带两个参数类型为T的函数hy。

演示示例:

TemplateDemo.h

复制代码

1 #ifndef TEMPLATE_DEMO_HXX

2 #define TEMPLATE_DEMO_HXX

3

4 template<class T> class A{

5 public:

6 T g(T a,T b);

7 A();

8 };

9

10 #endif

复制代码

TemplateDemo.cpp

复制代码

1 #include<iostream.h>

2 #include "TemplateDemo.h"

3

4 template<class T> A<T>::A(){}

5

6 template<class T> T A<T>::g(T a,T b){

7 return a+b;

8 }

9

10 void main(){

11 A<int> a;

12 cout<<a.g(2,3.2)<<endl;

13 }

结构-struct

在c++中struct和类的区别在于struct不能有方法,所有成员是public的

struct Movie/*可以指定类型名也可以不指定*/

{

//成员都是public的

int ID;

string Name;

} movie; //可以在声明struct的时候声明一个struct实例,这个有啥意思呢?

int main(){

//movie变量在Movie结构声明处定义了

movie.ID = 100;

movie.Name = "Face Off";

cout<<"movie.ID = "<<movie.ID<<endl;

cout<<"movie.Name = "<<movie.Name<<endl;

//声明一个变量m,无须为赋初值就可以使用它了

Movie m;

m.ID = 101;

m.Name = "多面双雄";

cout<<"m.ID="<<m.ID<<endl;

cout<<"m.Name="<<m.Name<<endl;

//声明结构的指针

Movie * mp;

mp = &m;

//在指针中调用成员时要用->符号,mp->ID等价于(*mp).ID

cout<<"mp->ID = "<<mp->ID<<endl;

cout<<"mp->Name = "<<mp->Name<<endl;

}

其他小知识点

1. 常用的#include头文件总结

STL = Standard Template Library,标准模板库

#include <limits> //定义各种数据类型最值常量

#include <map> //STL 映射容器

2.”using” keyword in C++

Usage

- using-directives for namespaces and using-declarations for namespace members

- using-declarations for class members

- type alias and alias template declaration (since C++11)

using namespace std; // to import namespace in the current namespace

using SuperClass::X; // using super class methods in derived class

using T = int; // type alias

A typedef-name can also be introduced by an alias-declaration. The identifier following the using keyword becomes a typedef-name and the optional attribute-specifier-seq following the identifier appertains to that typedef-name. It has the same semantics as if it were introduced by the typedef specifier. In particular, it does not define a new type and it shall not appear in the type-id.

this pointer

Syntax

this

The keyword this is a prvalue expression whose value is the address of the object, on which the member function is being called. It can appear in the following contexts:

- Within the body of any non-static member function, including member initializer list

- within the declaration of a non-static member function anywhere after the (optional) cv-qualifier sequence, including dynamic exception specification(deprecated), noexcept specification(C++11), and the trailing return type(since C++11)

- within default member initializer (since C++11)

The type of this in a member function of class X is X* (pointer to X). If the member function is cv-qualified, the type of this is cv X* (pointer to identically cv-qualified X). Since constructors and destructors cannot be cv-qualified, the type of this in them is always X*, even when constructing or destroying a const object. When a non-static class member is used in any of the contexts where the this keyword is allowed (non-static member function bodies, member initializer lists, default member initializers), the implicit this-> is automatically added before the name, resulting in a member access expression (which, if the member is a virtual member function, results in a virtual function call).

In class templates, this is a dependent expression, and explicit this-> may be used to force another expression to become dependent.

During construction of an object, if the value of the object or any of its subobjects is accessed through a glvalue that is not obtained, directly or indirectly, from the constructor’s this pointer, the value of the object or subobject thus obtained is unspecified. In other words, the this pointer cannot be aliased in a constructor:

extern struct D d;

struct D {

D(int a) : a(a), b(d.a) {} // b(a) or b(this->a) would be correct

int a, b;

};

D d = D(1); // because b(d.a) did not obtain a through this, d.b is now unspecified

Example

class T

{

int x;

void foo()

{

x = 6; // same as this->x = 6;

this->x = 5; // explicit use of this->

}

void foo() const

{

// x = 7; // Error: *this is constant

}

void foo(int x) // parameter x shadows the member with the same name

{

this->x = x; // unqualified x refers to the parameter

// 'this->' required for disambiguation

}

int y;

T(int x) : x(x), // uses parameter x to initialize member x

y(this->x) // uses member x to initialize member y

{}

T& operator= ( const T& b )

{

x = b.x;

return *this; // many overloaded operators return *this

}

};

class Outer {

int a[sizeof(*this)]; // error: not inside a member function

unsigned int sz = sizeof(*this); // OK: in default member initializer

void f() {

int b[sizeof(*this)]; // OK

struct Inner {

int c[sizeof(*this)]; // error: not inside a member function of Inner

};

}

}

auto specifier

auto specifier (since C++11)

For variables, specifies that the type of the variable that is being declared will be automatically deduced from its initializer. For functions, specifies that the return type is a trailing return type or will be deduced from its return statements (since C++14). for non-type template parameters, specifies that the type will be deduced from the argument (since C++17)

Syntax

- auto variable initializer (1) (since C++11)

- auto function -> return type (2) (since C++11)

- auto function (3) (since C++14)

- decltype(auto) variable initializer

#include <iostream>

#include <cmath>

#include <typeinfo>

template<class T, class U>

auto add(T t, U u) -> decltype(t + u) // the return type is the type of operator+(T, U)

{

return t + u;

}

auto get_fun(int arg) -> double (*)(double) // same as: double (*get_fun(int))(double)

{

switch (arg)

{

case 1: return std::fabs;

case 2: return std::sin;

default: return std::cos;

}

}

int main()

{

auto a = 1 + 2;

std::cout << "type of a: " << typeid(a).name() << '\n';

auto b = add(1, 1.2);

std::cout << "type of b: " << typeid(b).name() << '\n';

auto c = {1, 2};

std::cout << "type of c: " << typeid(c).name() << '\n';

auto my_lambda = [](int x) { return x + 3; };

std::cout << "my_lambda: " << my_lambda(5) << '\n';

auto my_fun = get_fun(2);

std::cout << "type of my_fun: " << typeid(my_fun).name() << '\n';

std::cout << "my_fun: " << my_fun(3) << '\n';

// auto int x; // error as of C++11: "auto" is no longer a storage-class specifier

}

Possible output:

type of a: int

type of b: double

type of c: std::initializer_list<int>

my_lambda: 8

type of my_fun: double (*)(double)

my_fun: 0.14112